A close friend of mine, an English teacher who possesses the extraordinary power of making literature feel vibrant and dynamic, once inherited a notoriously boisterous Year 9 class. They were labelled underachievers, the kind of class that staffroom lore had already written off. The prevailing advice was to keep things simple with them. Choose “accessible” texts. Avoid anything too abstract. Prioritise behaviour first and ambition second. But he refused to lower the intellectual bar. Instead, he began the year by placing in front of them a poem dense with metaphor, emotional nuance and complex imagery. These were students who had rarely been asked to look beneath the surface of a text. Yet he insisted on treating them as capable thinkers.

He refused to settle for worksheets compiled as busywork. He refused to strip the curriculum of its complexity. He held his ground when told the text was too difficult, that these students needed something friendlier, simpler, more manageable. He believed, without compromise, that if he scaffolded the journey, his students could climb. He spent weeks modelling how to sit with a line of poetry, how to unpick a metaphor slowly, how to make meaning through dialogue, gesture, and personal response. He reached into emotional spaces often dismissed as too risky for these students. In doing so, he showed them that great literature was theirs to claim.

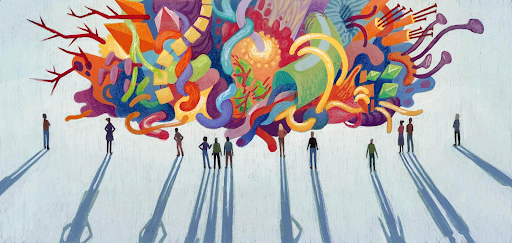

This is the heart of the degree of difficulty. It is the belief that challenge is not the enemy of success, but the engine of it. It requires us to hold our nerve as educators, to resist the pull toward simplification, and to retain complexity in our curriculum because complexity is where deep learning lives.

Degree of Difficulty and Holding High Expectations

The starting assumption must be that no text is too hard for students to access. The moment we decide that certain works are beyond them, we confining students to a leaner, less nourishing body of knowledge. Instead of replacing difficult material with something easier, we should provide multiple entry points that allow all learners to grapple with challenging ideas. This does not mean leaving students unsupported. It means designing scaffolds that bring them into the richness of the material.

Mary Myatt articulates this clearly. She writes that what truly matters is ensuring that “pupils with lower starting points are not offered a diminished diet, but rather are supported to access demanding work, through appropriate scaffolding and support.” Scaffolding is a moral imperative. An ambitious curriculum is one in which challenge is deliberately curated, and difficulty is not avoided but embraced.

One practical way of doing this is to build a collection of demanding resources. Academic texts, primary documents, journal articles and original sources offer students contact with authentic disciplinary thinking. To break the intimidation barrier, teachers can begin with abstracts and conclusions, or divide the text into short, digestible sections. Students might identify a thesis, highlight main arguments or pull out evidence in small groups. These are manageable cognitive steps that maintain the integrity of the material.

Graphic organisers can help, but they must be designed thoughtfully. Their purpose is to clarify complexity, not to simplify it until nothing remains. Instead of presenting organisers as a hierarchy of knowledge, teachers can create prompts, symbols and visual cues that invite students to expand the ideas themselves. Better still, students can construct their own visual representations, shifting the intellectual responsibility back onto them.

Critical Thinking Cannot Be Taught Without Complexity

A curriculum stripped of difficulty is a curriculum that cannot cultivate critical thinkers. Daniel Willingham’s work is central here. In his review of research on critical thinking, he concluded:

“First, critical thinking, as well as scientific thinking and other domain based thinking, is not a skill. There is not a set of critical thinking skills that can be acquired and deployed regardless of context. Second, there are metacognitive strategies that, once learned, make critical thinking more likely. Third, the ability to think critically depends on domain knowledge and practice”

Willingham, 2007, p. 17

Willingham’s insight is clear. Critical thinking cannot exist without rich, domain-specific knowledge. Students need to build schemas within disciplines before they can reason within them. The best way to do this is through sustained engagement with challenging materials. When students encounter complex texts, knotty ideas and unfamiliar vocabulary, their cognitive architecture grows. They learn to make connections, evaluate evidence, and exercise metacognitive control. They begin to understand how experts in a field think.

Our task then is not to simplify content, but to design systems and routines that help students access it. Reading protocols, question stems, annotation frameworks, structured discussions and collaborative routines all create the cognitive conditions in which challenge can thrive.

Creating an Ecosystem of Complexity

When we talk about complexity in the curriculum, we are not talking about difficulty for its own sake. Complexity must be purposeful. It must be the type that deepens conceptual understanding and builds long-term mastery. Creating an ecosystem of complexity means designing a curriculum where difficult materials are the norm, not the exception. Students learn that challenge is not something to fear, but something to expect.

Overarching curriculum challenges can frame this work. These challenges are often big questions, conceptual provocations or generative ideas that pull students into intellectual struggle. They give purpose to the difficulty. Alongside them sit the think-hard resources, the demanding texts, and the sophisticated problems that require interpretation, synthesis and evaluation.

Inspection and reflection are vital here. Students need tasks that help them evaluate evidence, compare sources and strengthen their decision-making skills. They need regular opportunities to rehearse disciplinary habits, such as citing evidence, questioning assumptions and revisiting interpretations. With routine exposure to complexity, they become more fluent in navigating it.

The Discipline of Expectation

At the centre of the degree of difficulty is expectation. Students often rise or fall to the level of the expectations held for them. The highest expectations require belief, courage and pedagogical precision. My English teacher friend knew this. He taught with the assumption that every student had the right to encounter beauty, nuance and layered meaning. He refused to simplify the curriculum because he understood that difficulty, when supported, invites growth.

Educators must be custodians of intellectual challenge. We must create the conditions in which each learner engages with the fullness of a discipline, not a diluted approximation of it. Complexity is not elitist. It is democratic. When taught well, it gives every student access to the deepest work of thinking.

Holding onto Complexity in the Curriculum

Retaining complexity in the curriculum is not simply a pedagogical choice. It is an ethical one. Providing students with intellectually demanding material, supported through thoughtful scaffolding, is how we nurture resilient, curious and capable learners. The degree of difficulty is a commitment to seeing students not as fragile, but as powerful thinkers in the making.

My friend’s Year 9 class eventually became one of his most engaged groups. They debated interpretations, challenged one another, argued fervently over metaphorical meanings and found themselves returning voluntarily to difficult poems long after the unit was over. They rose to the challenge because the challenge belonged to them.

A curriculum that embraces difficulty invites that same transformation in every classroom. It allows students to grow into thinkers, creators and disciplinarians who are equipped to wrestle with complexity, not avoid it. When we hold onto the difficult, we hold onto the possibility of brilliance.

References

Christodoulou, D. (2014) Seven Myths About Education. London, Routledge.

Counsell, C. (2018) ‘Taking curriculum seriously’, Impact, 2(5), pp. 6–12.

Education Endowment Foundation (2023) Improving Literacy in Secondary Schools. London, EEF.

Myatt, M. (n.d.) High Challenge, Low Threat. Available at: https://marymyatt.com

Willingham, D. (2007) ‘Critical thinking: Why it is so difficult to teach’, American Educator, 31(2), pp. 8–19.

Young, M. (2014) Knowledge and the Future School: Curriculum and Social Justice. London, Bloomsbury.