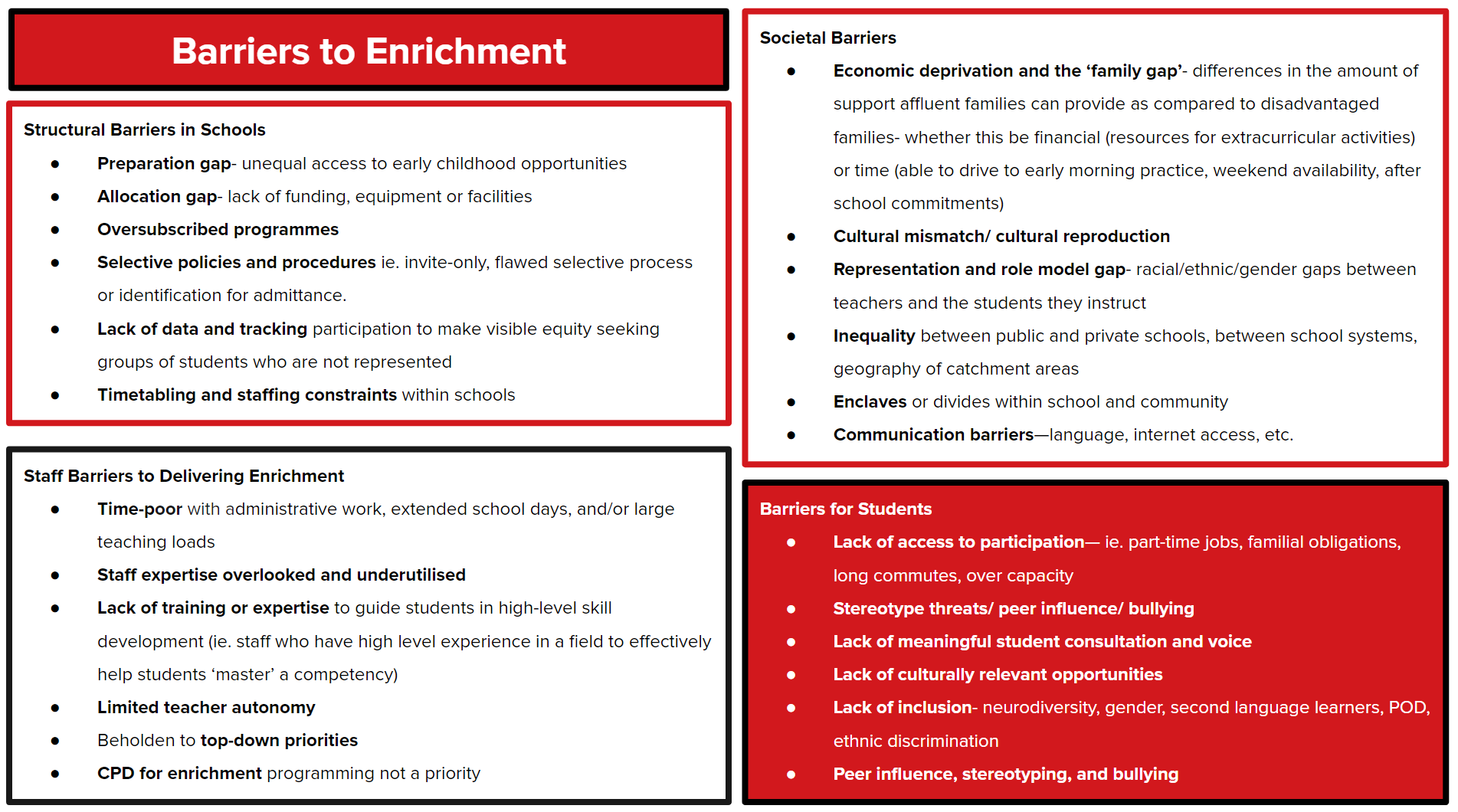

Let’s say I give a keen geography student a referral to the school’s Model United Nations Club, this seems like a wonderful way to extend their curiosity and development beyond the curriculum. However, there could be a lack of financial ability to pay for trips and conferences, or a lack of time for a student to participate because they work at a part-time job after school. A bully could impact their well-being, or an injury could derail their participation. Teachers, siblings, and peers can exert a positive or negative influence. A school may not have a Model UN provision due to a lack of funding, lack of student interest, or lack of experienced teachers to lead. Independent deliberate practice on the part of a student is possible, however, access to programs and guidance from experts is key for skills development

Chance encompasses the ‘where, what, and when’ that presents some individuals with more opportunities than others. ‘Chance’ is compelling as a catch-all phrase, however, it should not imply that success is a roll of the dice, we should not frame educational structures as passive inheritors as opposed to perpetrators. The chance of living near a school with an open enrichment program, the chance of being in the right catchment area, and the chance of having an enthusiastic mathematics teacher who leads an award-winning Mathletes team, are all ways a child could be lucky. There is also the chance of being thwarted and having barriers that block the progression of gifts into reaching fruition as talents.

“Chance” is a benign way of whitewashing structural inequity.

Purdue University’s Gifted Education Research and Resource Institute concluded in a shattering and extensive 2019 publication that advantaged schools identified more children as gifted than underfunded ones, with students of colour being underrepresented across the board (Gentry, 2019). The Purdue study determined that whether a child is identified with gifts and talents was largely determined by three structural forces:

- Access: A child must attend a school that identifies students as gifted to provide them with provision, and in 2019, more than one-third of children in the U.S. did not attend such schools. In the 2015-16 school year 42% of schools did not identify a single student with gifts or talents.

- Class: Children who attend non-wealthy (Title I) schools are identified at only 58% of the rate of those who attend wealthier (non-Title I) schools.

- Race: Children who are Asian or White are 2 to more than 10 times more likely to be identified with gifts and talents than students who are Indigenous American, Indigenous Hawaiian/ Pacific Islander, Black, or Latin American.

Chance is the lived experience of structural inequality. It is our environment, part of the larger geographic, demographic, and sociological picture. This is where class, race, ethnicity, and gender bias come into play. I would point to studies that look more specifically at the socio-economic context. Gymnastics is often cited as a prohibitively expensive sport. Parents must be able to afford the uniforms, camps, gym fees, coaching fees, transportation, and hotel costs for competitions, and have access to great medical care. This is on top of having the time to transport their child to early morning practices and commit to weekend travel. Parents’ ability to support their children may be constrained by work or familial commitments.

Out-of-school programming is one of the most common ways to implement enrichment. Students benefit from exposure to new activities, mentorship, exploration outside the curriculum, opportunities to practice new skills and develop independence. Schools that emphasize cognitive ability testing tend to perpetuate a ‘nature’ first argument, with gifts to be developed. We can’t fix the element of chance but we can see the inequity it creates and adapt. Understanding racial barriers, class differences or gender bias is part of making education inclusive. On the surface, it can look like school enrichment is open to all—this may stem from the fact that there is no explicitly selective gifted programming, or that programming is done through student self-selection.

Worrell and Dixson have commented that we should focus less on early identification for gifted programming and more on providing quality educational opportunities to as many students as resources allow before societal inequalities start to compound. The structures of our schools and the decisions we make in creating programs have a tremendous impact. James Borland makes the argument that gifted programs are often held back from the least advantaged students who, if they had access, the programs could make the largest impact.

Given how mutable a ‘gift’ is, enrichment programming starts with the premise that anyone can toss their hat in the ring. We have seen the disadvantage a student has when throwing their hat in from the back benches. It is a daunting task to overcome barriers. So we should explore how we can place every child in a favourable position by creating equitable environments. This begins with policies, processes, investment, and a mission to create inclusive enrichment opportunities.

References

Borland, J. H. (2004) Issues and practices in the identification and education of gifted students from under-represented groups. New York, NY: Teachers College, Columbia University.

Gentry, M., Gray, A. M., Whiting, G. W., Maeda, Y. and Pereira, N. (2019) ‘System failure: access denied gifted education in the United States: Laws, access, equity, and missingness across the country by locale, Title I school status, and race.’ Compton, L. (Ed.) United States of America: Purdue University.

Worrell, F. C. and Dixson, D. D. (2022) ‘Achieving equity in gifted education: Ideas and issues.’ Gifted Child Quarterly, 66(2): pp. 79-81.