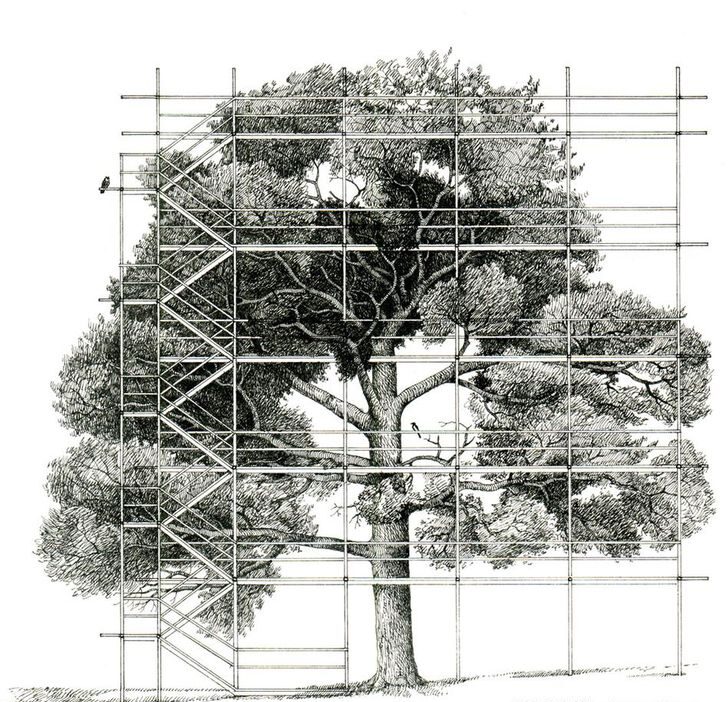

Adaptive teaching relies on scaffolds. In fact, Alex Quigley has written about how necessary they are as part of the 4 S’s of Adaptive Teaching- Scaffolds, Scale, Structure and Style. Let’s explore further how we can best create and deploy scaffolds that enhance adaptive teaching. We do not want to fall into the trap of designing separate differentiated resources for 28 pupils, yet the goal of adaptive teaching is to individualise instruction.

Great scaffolding is about building procedural knowledge. Hence a scaffold is used throughout a series of lessons or unit of work, not a one-off support for a task in a single lesson. A great scaffold can be a framework a student will continue to use over several years. Consider a scaffold through backwards design, what is the end product we want students to create? How are we building a scaffold that can be used throughout the curriculum? The goal is for the procedural knowledge to be automatic.

Scaffolding is an important facet of adaptive teaching, quality resources are ones that ‘scaffold up’ and are used responsively, as opposed to by default. Differentiation would ask for scaffolding to be provided for targeted students, this is useful when differentiating the support (not the outcome, as the same high expectation for a product is given to everyone). Universal Design for Learning would ask that we have an environment where scaffolding is available to all students, as many could benefit beyond those identified with an additional educational needs. The difference with adaptive teaching is that high expectations, productive struggle and individualised guidance are at the forefront of instruction.

This would mean that a great scaffold reinforces all three of those elements: the scaffold is the blueprint for high expectations, a tool for individualised guidance and the framework for questions and tasks for when students productively struggle.

High Expectations

High expectations must be modelled. Before a scaffolded resource is used, we first can present an exemplar that demonstrates the high expectations we have and how to get there. Guided modelling begins with a model for all. This is as simple as I do, we do, you do with examples. ‘I do’ can be for the whole class or in small groups. After the teacher models the ‘I do’ there is gradual release. We can activate peer learning and have the ‘we do’ in pairs of flexible groupings, the ‘you do’ is tackling the task individually. This is a ‘live writing frame’ that insists on practice before the task and reinforces the chunking of steps. Then there are repeated opportunities to model and label the expert processes.

For example, let’s say in English we want students to learn how to approach an essay task (answer the question, label the technique, give evidence, explain how the evidence fits with your answer, narrow down to a single word or phrase, explore the connotations and various inferences, link, talk about the readers’ feelings and the author’s purpose). What is an effective writing frame? Over a scheme of work, you would explain each step, practice each step in isolation, see an exemplar, identify components in the exemplar, complete a half-finished model, attempt an essay in full, reflect, critique and improve through practice. The aforementioned essay-writing steps are the overarching scaffold and larger learning intention.

Individualised Guidance

Students will be at different points, so the level of challenge in terms of starting points varies. Pre-requisite checks provide a good understanding of the baseline of all students. Frequent formative assessment is vital throughout adaptive teaching.

In the example of the writing frame within adaptive instruction, this would be offered if a teacher has conversed with a student and determined that this is the resource they would find useful to overcome a specific barrier in a task. The emphasis is on being present with that student, asking them to articulate the blockage and listening to give the appropriate support. This is replacing the paradigm of preparing many many many differentiated resources that take up teacher planning time and do not necessarily meet the exact needs of a student at that moment.

Walk around first. A teacher can have a scaffold available, that is anticipatory. However, the idea is that you are responsive in the moment with no assumptions that a student can or cannot do something. Instead, you are asking them to authentically engage with the task first and given them the opportunity to struggle. When they are stuck, ask them what about the task they find challenging. Making students be specific in their struggle requires them to articulate their learning barrier, it also allows you to assess correctly- what metacognitive strategy do they need? What are the mechanics of the task they may require? Is there prior knowledge they are missing to complete the task? Or is there an issue of confidence for a fragile learner? Assessing is key, a student not knowing how to spell an unfamiliar word or the meaning of a disciplinary term will not be helped by a writing frame. Waiting is also key, we don’t want to step in too soon- although there is a massive temptation to help students instead of allowing for that all-important productive struggle!

Productive Struggle and Gradual Release

A scaffold is a structure that can be taken down eventually because students know how to build it themselves. It is important that we give them the tools to take that scaffold down, practicing without it, so they become self-reliant and the procedural knowledge is embedded. A great scaffolded resource requires engagement and is not a stagnant reference. Checklists allow students to identify exactly which step they are struggling with and what steps they are already capable of. As a bonus, checklists allow students who have already acquired the necessary learning skills can accelerate ahead.

We can twist the scaffold, instead of a fill-in-the-blank writing frame, give students a list of actions and ask them to put that mixed-up checklist in the correct order. If you give students an exemplar, have them identify the steps and label components in the exemplar before attempting their own. In adaptive instruction we want elements of self-direction and an environment of choice- dictionary corner, ‘we do’ table to trial in pairs, metacognitive reflection hints on the wall, deep dive stations for extended reading, etc. For instance, in lieu of asking a teacher about the unfamiliar disciplinary term they should be asking a peer, or going through their knowledge organiser. We want to encourage ‘the learning pit’ so students ‘know what to do when they don’t know what to do’. So when the teacher is busy with another group they have places to go and strategies to help themselves.

All in all, a great scaffold is procedural knowledge that is used over an extended stretch of curriculum. In adaptive instruction this scaffold is for imparting longlasting, procedural knowledge over a series of lessons for gradual individually paced release.