It began with a chance encounter.

In the late 1920s, Ned Harkness, a shy boy who had grown up longing for classrooms where he could think aloud without fear, boarded a train that would change the trajectory of American education. By luck, he met Dr Lewis Perry, the principal of Phillips Exeter Academy. Curious about Perry’s work, Harkness asked a simple but disarming question: was the current education system truly serving every child?

What followed was not small talk but a profound conversation about schooling, equity and human potential. Perry lamented that traditional classrooms, practices rooted in recitation and rote, were no longer fit for purpose. Harkness, who understood what it meant to be overlooked or drowned out in conventional classroom hierarchies, pressed further. He wanted an education system in which every student, regardless of personality, background or confidence, could contribute meaningfully. He wanted a circle where shy children, like he once was, could find safety and voice. The two men became fast friends, united by a shared belief that learning should feel more like conversation than compliance.

Ned Harkness, a rich philanthropist, wished to invest. Perry returned to Exeter determined to act. Harkness envisioned a transformation “so different from methods prevailing here that, were they adopted, the whole educational system would not only be changed, but changed enormously for the better.”

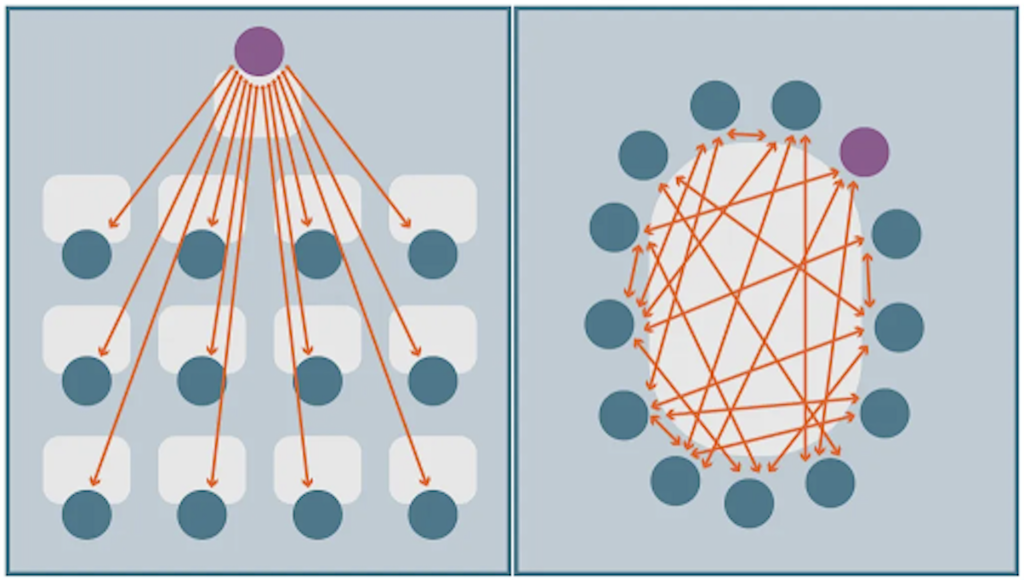

Perry went to the drawing board. After six months of committee work, he returned with a bold plan, to dismantle the teacher-centred classroom entirely and rebuild it around a single, elegant piece of furniture, the Harkness table. An oval table seating ten to twelve students, with no head and no hierarchy. A space where young people would learn not by receiving knowledge, but through dialogue, inquiry, debate and collective meaning-making.

Harkness loved it. New buildings, smaller class sizes and rooms filled with handmade oak tables became the physical markers of a philosophical shift, learning as relationship, thinking as collaboration and discussion as the vehicle for deep intellectual engagement.

Nearly a century later, the Harkness Method remains one of the most powerful models of student-led discourse. Yet its magic is not the table itself. It is the culture around it. It is the intentional scaffolding, the slow teaching of listening skills, the cultivation of intellectual humility and the willingness of teachers to relinquish control. At the heart of this practice is a deceptively simple pedagogical move that holds everything together.

The Importance of the Pause

“The pause” is one of the most radical features of the Harkness Method.

It is the moment when teachers resist the instinct to lead, to rescue, to redirect or to fill silence with explanation. It is a professional discipline, an intentional stepping back that signals deep trust in students and in the process of learning. Silence becomes generative. It creates space for students to enter, to take risks, to connect ideas and to respond to one another.

One English teacher captured this beautifully, in Harkness, “you subordinate your critical agenda for a belief in the process. You have to fundamentally believe that what the kids are getting at the table, out of wrestling with complexity and talking to each other, is more important than making sure they understand what the green light is in Gatsby” (Soutter and Clark, 2021, p. 5).

The pause decentralises authority. It shifts students from passive participants to intellectual agents. It makes room for authentic, student-to-student dialogue.

This is not the Socratic method, where the teacher questions and leads students toward a predetermined insight. A true Harkness discussion is horizontal, shared and co-constructed. Polm (2019) notes that the richest discussions occur not between teacher and student, but between students themselves.

For teachers accustomed to facilitating, the pause can feel uncomfortable at first. But it is a powerful statement, I do not need to hold the floor. This learning belongs to you.

Photo Image: Philips Exeter Academy

Building the Conditions, Scaffolding for Authentic Dialogue

Harkness discussions appear effortless when done well, but the ease is deceptive. They require meticulous scaffolding. Listening skills, respectful dialogue, evidence-based argumentation and collaborative reasoning do not emerge overnight. They must be taught, rehearsed and refined.

1. Establishing Norms and Psychological Safety

The foundation lies in clear, co-constructed discussion guidelines. Students help articulate how they will listen, respond, challenge and build on each other’s ideas. These norms are revisited often. Teachers rehearse small routines, turn-taking, summarising or inviting quieter voices, until they become habitual. Lancaster (2020) describes this as cultivating “routine respect”.

The environment must feel safe for intellectual risk-taking. Normalised disagreement is encouraged. Students learn that well-reasoned dissent is not conflict but contribution.

2. Designing Rigorous Resources

The quality of a Harkness session rests on the quality of the material students bring. Teachers curate problem sets, readings and prompts that require slow thinking and independent preparation. Backwards design helps ensure that the resources build toward conceptual richness rather than superficial recall.

The aim is challenge first. Students arrive at the table with ideas to test, questions to explore and evidence to defend. Complexity in the reading diet produces complexity in discussion.

3. Preparation, Accountability and Goal-Setting

Like the Oxford tutorial system that inspired elements of Harkness, students are expected to prepare deeply and independently. They set personal goals, “ask three open-ended questions”, “build on a peer’s point”, “cite two pieces of evidence”, and evaluate themselves after each session.

Group goals can elevate the entire conversation, “everyone cites evidence”, “we build links to our last topic”, “we identify a counterargument”.

These metacognitive practices cultivate self-regulation and shared responsibility.

4. Student Facilitation, Distributing Power

One misconception is that Harkness discussions require the teacher to act as facilitator. In truth, we are teaching students to facilitate themselves. They can draft agendas, pose initial questions, moderate exchanges and map the flow of the conversation.

As Shapiro (2024) emphasises, the moderator “is not the de facto central teacher”, but the organiser of intellectual energy.

Distributing power distributes responsibility. Students are not passive recipients. They curate the dialogue.

5. Discussion Roles and Explicit Teaching of Moves

Teachers may initially assign roles, questioner, researcher, synthesiser, challenger, to scaffold participation. Over time, these roles fade as students internalise them.

Discussion strategies can be explicitly taught:

• declarative statements to launch new lines of thought

• reflective statements to deepen ideas

• dissenting statements to introduce challenge

• invitations to elaborate to clarify reasoning

• evidence-citing statements to ground analysis

Confusion is framed not as failure but as inquiry. A student admitting, “I do not understand this part”, can pivot an entire discussion.

6. The Teacher’s Subtle Moves

Though the teacher steps back, their role is far from passive. They must track the dynamics of the room, listen for misconceptions and intervene lightly when necessary. Techniques such as “deny the eye”, looking away from the speaker, signal that students should address peers, not the teacher.

When misconceptions arise, teachers resist correcting immediately. Instead, they wait to see whether a peer offers clarification. If not, the teacher may pose a question that nudges students back to the text or original prompt.

7. Evidence and Academic Accountability

High-quality Harkness discussion is grounded in textual or disciplinary evidence. Students must justify claims, interrogate source validity and resist cherry-picking. This builds intellectual rigour and prevents superficial consensus.

8. The Debrief, Learning How to Learn

Every session ends with reflection. Students consider what went well, what they contributed and what they may refine next time. As Michaels, O’Connor and Resnick (2007) outline, productive talk involves accountability to community, accountability to knowledge and accountability to reasoning.

Debriefing reinforces these dimensions and turns each discussion into a metacognitive milestone.

Tracking, Mapping and Rethinking Participation

Discussion tracking is one of the most powerful tools for teachers. Bird’s-eye diagrams, time-speaking graphs, body language trackers and comment-coding tools reveal patterns invisible in real time (Phillips Exeter Academy, n.d., Equity Maps, 2016).

These tools help answer crucial questions:

• Who speaks the most

• Who speaks least but contributes depth

• Which contributions moved the discussion forward

• Where did the conversation stall, splinter or soar

Lancaster (2020) and Mullgardt (2008) note that meaningful contributions include citing evidence, synthesising ideas, transitioning between points and challenging assumptions. Non-meaningful contributions, interruptions, rambling, rehearsed readings, are recorded not to shame but to guide growth.

Tracking allows teachers to “shut up and listen more”, as you observed. It reveals the relational architecture of a classroom, who trusts whom, who defers to whom, who amplifies whose ideas. This information is invaluable for designing next steps.

A Revolution Rooted in Relationship

The Harkness Method was never just about a table. It was about transforming the ecology of learning. Harkness believed, long before the language of student agency became popular, that young people are capable of profound thinking when given structure, space and trust.

At the table, students look at one another directly. There is nowhere to hide, but equally, nowhere to disappear. The circle flattens hierarchy and redistributes intellectual authority. It demands presence, attention and mutual respect.

In a world that increasingly prizes collaboration, critical thinking and communication, the Harkness Method feels not only timeless but urgent. It teaches students how to listen deeply, question courageously and contribute responsibly. It cultivates intellectual autonomy while nurturing community.

Harkness sought to “revolutionise education” for shy children who needed safer, richer spaces to grow. Nearly a century later, his revolution still matters. It reminds us that learning is a shared act. Sometimes, the most powerful thing a teacher can do is pause, step back and let students take the lead.

References

Equity Maps (2016) Equity Maps iPad App. Available at: https://equitymaps.com

Lancaster, J. (2020) The Harkness Method: A Practical Guide for Teachers. London, Self-published.

Michaels, S., O’Connor, C. and Resnick, L. (2007) Deliberative Discourse Idealized and Realized: Accountable Talk in the Classroom. Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh.

Mullgardt, J. (2008) Harkness Teaching in Practice. Exeter, Phillips Exeter Academy.

Phillips Exeter Academy (n.d.) Discussion Tracking Templates. Exeter, Phillips Exeter Academy.

Polm, K. (2019) ‘Student to Student Dialogue in Harkness Classrooms’, Journal of Teaching and Learning, 12(3), pp. 45–57.

Shapiro, S. (2024) Moderating for Meaning: Leadership in Student-Directed Discussion. Cambridge, Harvard Education Press.

Soutter, M. and Clark, E. (2021) ‘Subordinating the Agenda: Teacher Identity and the Harkness Table’, English Journal, 110(5), pp. 3–9.Towler, K. (2006) The Harkness Gift: A History of Innovation at Phillips Exeter Academy. Exeter, Phillips Exeter Academy Press.